di Laura Ferrarello

Image ⓒLaura Ferrarello

Leggi l’articolo in italiano qui

How can a business’s missions and visions harness sustainability as a strategy for creating value for the organization and benefits for society and the environment?

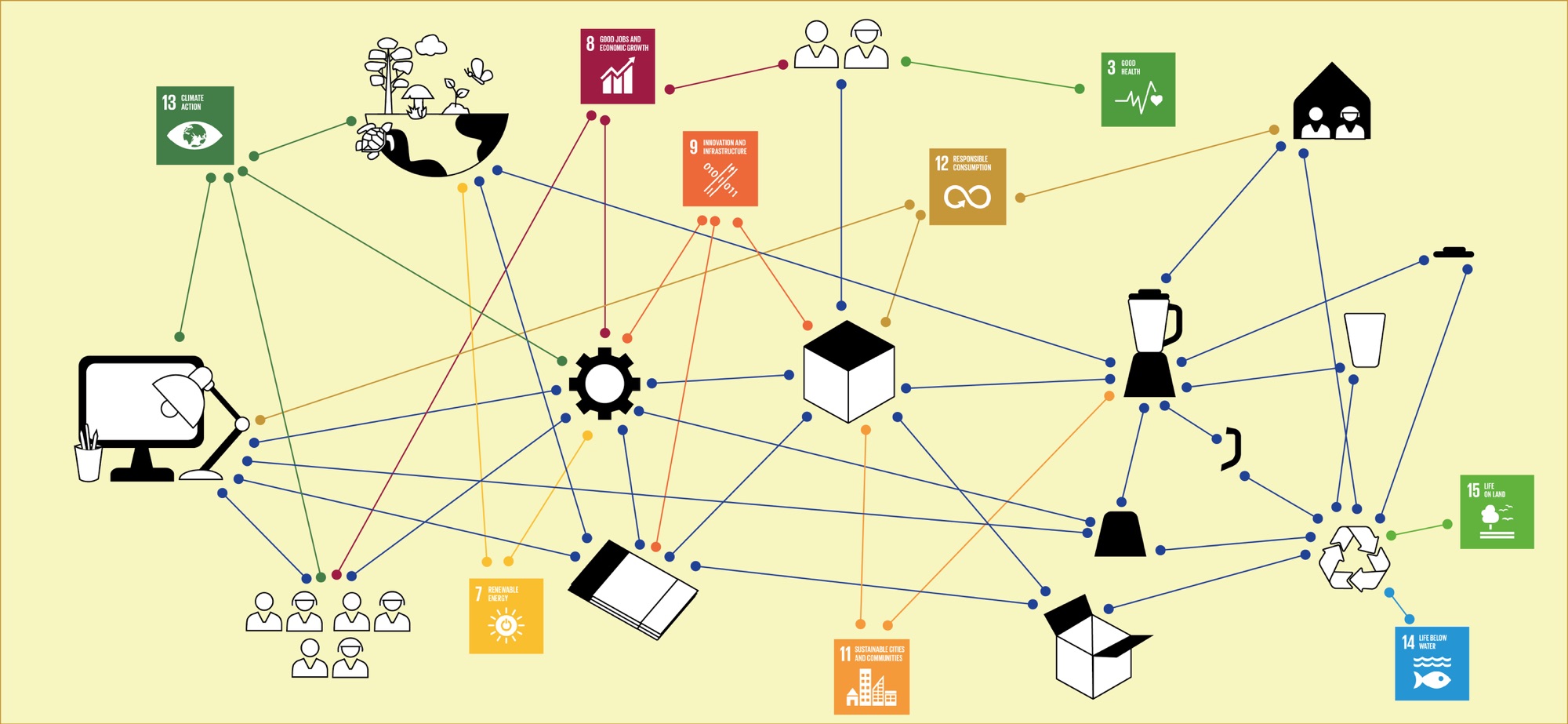

A business transition towards sustainable practices is a journey requiring systemic change. This is because to be effective, sustainability can’t be simply understood as a target to be achieved, but as a dynamic and fluid process that needs to be maintained with the alignment of different sections and departments of an organisation’s business ecosystem. This includes the products, services, or technologies that a business offers, but also the way they are produced, manufactured, distributed, used, and disposed, in terms of material usage and labour exploitation.

Sustainability: a strategic value for an organization

To leverage an effective sustainable transition, the organization’s values and culture could play a key role by guiding its different practices in pursuing diverse processes and procedures that are sustainable in their context. If the mission of an organization is to position its business in sustainable markets, this is a vision that any core operations should follow. For instance, a consumer product company could embrace a cycle type of economy by outsourcing certified materials and fair working contracts, by reducing variety for privileging local production, by designing products whose components can be easily replaced, with logistic chains integrating the reuse of product components, from manufacturing to return collection points. Any of these actions present different shapes of sustainability, I.e, fair work, respect for natural materials, priority of local knowledge and economy, reduced waste, or championing a consumer’s culture of responsible consumption.

Actioning sustainable mission through distributed systemic actions

To orchestrate such camouflaging meanings and shapes, the expression “sustainable business” would require a strategic definition that combines terminology familiar to the business practices with their sustainable opportunity. This would help any employee understand what it would entail adopting and privileging sustainable practices as a personal choice. Indeed, the impact of individual choices can ripple out to the community of employees sharing relatable actions. Here, regulations, process guidance, and recommendations on professional behaviour (e.g., acquiring natural materials, shipping modalities, manufacturing protocols, labour rights, consumption of energy across the value–chain) can guide staff in implementing visions, thus turning principles into actions.

As Donella Meadows explains through the 12 leverage points scale, systemic change can be achieved more effectively through values (leverage N.3), culture (leverage N.2), and paradigm shifts (leverage N.1). However, to operate at the level of these top three, it is necessary a process where rules, feedback, and goals are set across the different parts of a system. In the consumer product example, this would mean that achieving sustainable practices should be pursued through, for example, an increased use of reused parts over new ones (goal); by designing new products as objects that can be assembled with reused parts (rules), by privileging used over new at a logistic stage (feedback).

The shared responsibility of sustainable transitions

Sustainable transitions are processes where everyone is responsible for their implementation, and that require coordinated actions for the achievement of a “sustainable goal”. In this context, sustainability should not be approached as a factor that hinders innovation. Because of the need to rethink established practices and agendas, a sustainable transition is a process of innovation on its own. Innovating for developing new technologies, or materials, would be a reductive way of approaching innovation, as it limits its space of opportunities distributed across the system; here, employees can find alternative new ways of operating. Indeed, a business can innovate its sector by changing established practices that our planet can’t support any longer.

According to UCL Professor Mariana Mazzucato, a strategy for addressing the systemic complexity of sustainability is to put forward clear mission-driven agendas that are coordinated by different stakeholders across the system (e.g., private organisations, government, policymakers, the financial sector). Such coordination aims to align systemic actions towards achieving targets that meet specific goals, like the UN 17 Sustainable Development Goals. This means that achieving sustainable targets and actioning sustainable visions necessitate collaboration across different private or public sectors. Collaboration increases the feasibility of a vision by distributing missions like reducing the waste of natural materials, protecting the health and well-being of our society, reducing the risks of new pandemics, or, generally, ensuring the implementation of climate agenda across the whole system of actors involved in achieving such goals, from manufacturing to regulation.

It follows that meeting sustainable objectives should not be considered a burden that an organisation should feel solely responsible for; responsibility should be shared across the different stakeholders acting or that have an influence (direct and indirect) in a sector. This could open new business opportunities by identifying partners with whom relationships can be developed for implementing actions aimed at meeting different targets of the same mission, and goal.

Hence, a mission to achieve sustainable goals is a coordinated strategy that implements different actions within the business ecosystem; from ideation to manufacturing, distribution, (re)use and disposal.

People are the strategy for sustainable transitions

For organisations, a sustainability-driven mission is, therefore, a people–led systemic strategy. This guides the implementation of business–core missions through defined targets distributed across its ecosystem. These targets should be understood as parts of a “whole” “sustainable strategy” system, whose implementation can open new opportunities for new partnerships and innovation. With these, transforming business practice(s) towards sustainable and respectful ones can increase the overall well-being of our society and the planet.

Bibliografy and resources

- United Nation Department of Economic and Social Affairs

- Mariana Mazzucato mission-oriented innovation and industrial policy

- Donella Meadows Leverage points – places to intervene in a system

Biography Laura Ferrarello

Dr Laura Ferrarello is a Design Researcher. Her research uses design strategies to create dialogue between technology, society and the planet in ethical ways. Laura teaches the course The Practice of Ethics in Engineering Research at the Ecolè Polytechnique Fédèrale de Lausanne (EPFL). She created the online course on the Future Learn Platform – Ethical Practices to Guide Creativity & Innovation. She led and contributed to a wide range of interdisciplinary research projects with the industry, including British Airways, Fujitsu, Huawei, amongst others. She collaborated with organisations like UNESCO, Lloyd’s Register Foundation, and The Royal National Lifeboat Institution. Laura designs workshops, and presents research in leading institutions, including Harvard GSD, ETHZ, Imperial London, King’s College, Fudan University, Tongji University. She is co–author of the book “Engaging Design: Tools for design practices urging new forms of citizenships”, with Dr Robert Phillips (EPFL Quanto, forthcoming 2025).

Scrivi un commento